Terms of

Use

Submissions

~ By Courtesy of Others ~

They Will Come

By Everett A Warren

She walked to the cold shoreline, her head held high. A slave, they called

her,

but she was of a proud race. Her honey blond hair swirled in cascades

around

her, her long dress that swirled about her ankles plain in comparison.

Once it had been embellished and ornamented as if for a princess or a queen.

She

had torn them off with her bare hands, for they were not of her people.

He had

ordered the gown for her, and he pilfered his own treasury to supply

the

priceless gems and metals. For that alone, she knew the gown was

from Him, and

the worship of their one God was not the worship of her people.

She knew this,

and did not weaken, for she knew something else as well. They will come.

Slowly, she lifted the wooden pipes to her lips, her eyes upon the gray mist that blanketed and bedded down the waves. She sat upon the large rock that loomed above the pebbled beach. She had sat there many a night before. As she had so many times before, she began to play. She knew this, and so she came to play, for she knew something else as well. They will hear, and they will come.

The melody was sad, plaintive; the rhythm like to the tides that rattled through the rocks on the beach. Echoing hauntingly across the waves, the waves that almost, soon, would leave ice crystals behind. Autumn was no more than a word and a distant thought here. Summer had fled, and it would be Winter soon enough. She had been here so many years now. She did not know how many years it had been since her capture, but she knew with unerring faith that someday, however far away, someday they will come.

She could hear, over the rolling and splashing of the waters, the slap of oars on waves. Barely audible to most, so quiet were the reavers, but to one of their own, especially one waiting so long to be returned to her homeland, they sounded like the pealing of the large bells in the monastery tower. Through the fog and mist and icy haze the proud bow of a dragon boat loomed forth. The shields, mounted upon the gunwales, the sail furled, the longship slid across the waves as no other type of vessel ever had before and no others ever would. For if the Greeks believed in Neptune, the Norse had allied with him. Or, she smiled as she played, conquered him. She pulled a wisp of blond hair back from her lips. She knew all along, had told everyone who would listen and those who would not hear, that someday, no matter how far away, someday they will come.

"They will not come."

She felt hands upon her shoulders, and the longship dissipated into the fog like all those before. A tear rolled cold down her cheek and she pulled the set of pipes away from her lips. She wanted to shake away the hands, make him see that they had come, and he had better run or his head would ride upon their spears. His hands felt like poison spreading through her, trying to wring the lifeblood from her, his words cutting into her with their falsehoods. But she knew that they had not come.

"No, they are not here..." She brushed her hair back from her face once more, although there weren't any strands that bothered her. Her sleeve dried the tear, hid the evidence. She turned, twisting, and stood. Accordingly, he stumbled and fell, bruising knees and hands. She tossed her long locks and stepped around him. She turned back. "...they are not here yet. But they will come."

The cowled heads bowed down as she thundered past, head down, hands by her sides, clenched in anger. Soon they would begin their chanting or ceremony or whatever it was. They did not look at her, they did not meet her eyes. Even the others, small Gaelic boys or girls, some also here against their wills (or their guardians wills), bowed their heads as the brothers chanted their god down into them. She had been beaten when she first declined to partake in their rituals. Now they turned away, ignoring her. Ignoring her flagrant disrespect, as she chose a longer, winding route to the small cell that was her prison simply with the purpose of disrupting their service. It must have worked, for she heard that they thought their god was one of love and mercy, and she knew few of the monks had stock in either category. Forgiveness may have been a word they could pronounce, but for her they had always been exacting in their punishments and quite caustic of tongue.

Moments after she passed amongst them, the Father Abbot returned, still dusting dirt from hands and knees, his face red with fury. She had, the monks knew, got the better of him once more. Several smiled beneath their cowls, perhaps a couple out of all the brotherhood felt any remorse and pity, both for the girl, for her screams and cries would be felt if not heard, and for the Abbot, whose grunts of pleasure surely would be audible throughout the abbey, as they were most every night.

There was one night, not long afterward, that was different than all the

rest. For one night, the Father Abbot found nothing in her behavior that upset

him enough to rape her. For one night, the Father Abbot did not rape her for

avoiding him so as to avoid upsetting him. For this night, he let her alone,

left her to listen to the words of the fair haired boy. It was defeat, they

said. Not only had the Northmen withdrawn their last from the British Isles (or,

like the boy, choose to stay and become a Viking no more), but there was word

that Odin, Thor, and the like had fallen from favour, and that by and large the

Northmen followed the Christ now, and were no longer enemies. In disbelief, she

questioned and quizzed the young man, thinking him false, thinking anything but

the truth of his words. The words of the Abbot, said as he left her chambers,

for once without joining with her on her pallet. They will not come, he said to

her.

She piped that night, playing as she never had before. The music so beautiful and heart-wrenching that the monks and the servants and the blond messenger boy stood around her, on the rocky shores, tears streaming readily. The Father Abbot was wrath when he heard of her performance, and straight-away he went down to the shores.

"They will not come!" his voice boomed, echoing amidst the slow piping, thundering off the waves themselves. And as the waters shivered into icicles and then drew back into the deep, there could be heard the sound of armour clinking. "They will not come! Cease this music! Your heathen gods are dead and vanquished! The reavers have returned to the North. They will not come!"

She turned and fixed him with a stare, as cold as the water she stepped into. She did not fall as the freezing waves soaked her long dress. "They will come." She waded deeper and the Father Abbot, in desperation, almost charged into the ocean after her. His brother monks held him back, despite his ravings. All fell silent as the bow of the longship broke from the fog and haze. The oars drew in, and burly arms lifted her up to the deck. She smiled back at the livid Abbot. "They have come, and your child shall not."

The monks screamed and looked away as one of the reavers thrust a sword through her belly. Blood frothed from the wound, but she did not fall to her knees on the deck. The young blond boy did not turn away, did nothing but look into her eyes. She was no longer on the deck, for there was no deck, no boat, no reavers. She stood in the waves, icy water about her waist, blood flowing to the shore, staining the rocks. Her hands held out to the side, she fell forward into the waves, her body tossed ashore moments later.

The boy licked his lips in fear, for there was no mistaking the sword's wound, equally as there was no mistaking the absence of the sword, the Viking that had held it, and the boat itself. As the monks stood and crossed themselves and spoke prayer and blessing, the young blond boy saw the pipe floating in the waves, angling towards him, as if with a will. It was red now, red like her blood. This disgusted him, for he was not of warrior borne, and blood was not his stock in trade. Despite his revulsion, he found himself holding it to his lips and playing. The melody continued of its own accord.

The monks fell silent, prayers slipping from lips, hands falling to their sides, heads turning to look in shock at the young messenger boy.

"How dare you..."

And then, with a great thundering heard from afar, even the Father Abbot fell silent. From the fog and waves rose yet another phantasm, although this was not in the form of a longship, which until recent times, could be found so often in these waters, as if it was the craft's natural habitat. Thundering as if they rode the very firmament, came several winged horses, mounted each one with an armoured woman, save the last, which was riderless. They splashed down in the shallow surf, the monks having drawn back. Their faces showed fear and disbelief as the winged horses circled the fallen girl.

"Come Sister, for we have much yet to do before we return to the Hall on High."

And then, slowly, the girl stood. She smiled. "You have come."

"Yes, Sister, we have come for you at last."

The monks, those few not cowering, passed out, or died in fright, watched in absolute horror and terror as the girl, fully armed and equipped as the other Valkyrie maidens, leapt astride her mount and smiled at the Father Abbot. "They have come for me, as I have said. Fear not the Valkyrie, False Father, for they shall not slay you, nor shall they select you to join the Host on High in Valhalla, for neither are you warrior nor noble."

And then one monk, screaming gibberish, ran forward, seeking to prove them all phantasms and figments. He hit the flank of the winged horse and fell backwards, stumbling, but not quick enough to avoid a nip upon his shoulder, near to ripping his arm off. A moment later his misery and pain ended as the steed's hooves made short work of his head and chest. The waters once again bloodied, the Valkyrie turned seaward, Northward, and were off.

The young blond messenger boy forgotten, the monks argued amongst themselves, trying to fathom what had befallen them this night. Despite the Father Abbot's claim of the devil and witchcraft, and of illusions and phantasms, their dead brother and the missing captive provided hard evidence for arguments. But their night was not over, and their cacophonous arguments did not fade quietly to a confused peace. For once again that night the monks fell to a silence filled with horror and dread. On this occasion, they faced not the sea and mysterious phantasms, but they looked shoreward, pointing, gibbering and shaking in fear.

Somehow, silently, a group of Viking raiders, returning to their prized Northlands and cold pagan gods, had stumbled upon their abbey.

"Well, old man, it would seem you were right." The leader spoke to a wizened beggar man, one eye covered by a patch. His other eye glinted, caught the eyes of the messenger boy, and winked.

As blood flew and monks died, the boy cringed in the cold surf, hidden by the rocks, the noise of the waves hardly serving to drive out the screams of the monks. Knowing who it was who had one eye and could so command the Norse warriors, the young boy cried in anguish and fear. They had lied, they had told him Odin did not exist, that their Christ was the only god. He ripped the cross from his neck and stood to hurl it far out to sea.

A hand gripped his wrist.

"Do not cast that away so quickly."

The boy turned, knelt before Lord Odin.

"Humph." The single eye glared down at him. "On your feet, you are not a vassal or slave. Be proud of who you are."

"M...m...milord, I am n...not warrior-borne. I am..."

"A kind, peace-loving boy. Yes, I know. Should be more like you in this world. Ah well." The old man pulled his wide brimmed hat off and looked out over the fallen monks. Not a single warrior remained on the beach.

"W...what happened? Were they real?"

"Of course they were. Their longship is on the lee of the island. Doubtless they have finished looting the monastery and are already aboard and sailing for colder shores."

The old man did not look so old from this perspective. He took off his

eyepatch and winked at the boy again, with the eye that had been hidden.

"Now, now, no more of this Odin thing. I'm no more Odin than I am Thor, and

if you've ever met Thor you know there would be no mistaking his girth or his

laugh or his wrath. Come."

They found several of the monks alive, some badly injured, many dead. Only two monks were completely unharmed, and they woke from their daze as the young, long bearded, long brown haired man the boy had mistaken for an old, stubble chinned, gray haired Odin reached down and gently roused them. "Heal your brethren. Heal this place." Then he stood, turned to the boy, and held up the cross he had saved from the sea. "This is gold, and is heavy with blood. Perhaps you were right." The cross arced out over the waters, gleaming until it was far into the mists. "Here, wear this, instead."

The man slipped a thong off his neck. The cross that hung there was simple, little more than two splinters of olive wood. Slowly the man knelt before the boy. "Heal these men, heal this place, young Father Abbot." The monks heard this, paused for a moment in their work, and watched as the man leaned forward and brushed dirt, mud, and ice from the boy's boots.

"So often they do not hear, or do not listen to what I say. My words, the Word, become twisted and lead to this. You will trust and you will love, and through these simple practices, you shall teach. You have not many with you, for few survive this night, but I tell you the truth, if you believe, then they will come."

Slowly the man who was not Odin rose and walked back up the path to the smoldering remains of the abbey.

Copyright © 2000 Everett A Warren

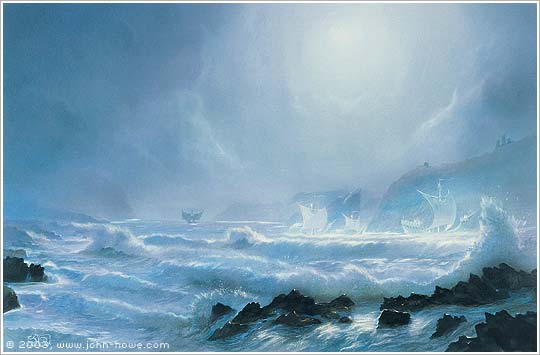

Image: "The Black Ship", © John Howe, www.john-howe.com